|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| otarafa: izlemeyennere | butarafa: forbidden zone |

|

A Wave of the Watch List, and Speech Disappears

|

|

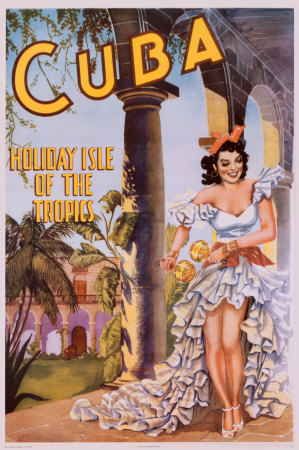

trips to Europeans who want to go to sunny places, including Cuba. In October, about 80 of his Web sites stopped working, thanks to the United States government. The sites, in English, French and Spanish, had been online since 1998. Some, like www.cuba-hemingway.com, were literary. Others, like www.cuba-havanacity.com, discussed Cuban history and culture. Still others — www.ciaocuba.com and www.bonjourcuba.com — were purely commercial sites aimed at Italian and French tourists. “I came to work in the morning, and we had no reservations at all,” Mr. Marshall said on the phone from the Canary Islands. “We thought it was a technical problem.” It turned out, though, that Mr. Marshall’s Web sites had been put on a Treasury Department blacklist and, as a consequence, his American domain name registrar, eNom Inc., had disabled them. Mr. Marshall said eNom told him it did so after a call from the Treasury Department; the company, based in Bellevue, Wash., says it learned that the sites were on the blacklist through a blog. Either way, there is no dispute that eNom shut down Mr. Marshall’s sites without notifying him and has refused to release the domain names to him. In effect, Mr. Marshall said, eNom has taken his property and interfered with his business. He has slowly rebuilt his Web business over the last several months, and now many of the same sites operate with the suffix .net rather than .com, through a European registrar. His servers, he said, have been in the Bahamas all along. Mr. Marshall said he did not understand “how Web sites owned by a British national operating via a Spanish travel agency can be affected by U.S. law.” Worse, he said, “these days not even a judge is required for the U.S. government to censor online materials.” A Treasury spokesman, John Rankin, referred a caller to a press release issued in December 2004, almost three years before eNom acted. It said Mr. Marshall’s company had helped Americans evade restrictions on travel to Cuba and was “a generator of resources that the Cuban regime uses to oppress its people.” It added that American companies must not only stop doing business with the company but also freeze its assets, meaning that eNom did exactly what it was legally required to do. Mr. Marshall said he was uninterested in American tourists. “They can’t go anyway,” he said. Peter L. Fitzgerald, a law professor at Stetson University in Florida who has studied the blacklist — which the Treasury calls a list of “specially designated nationals” — said its operation was quite mysterious. “There really is no explanation or standard,” he said, “for why someone gets on the list.” Susan Crawford, a visiting law professor at Yale and a leading authority on Internet law, said the fact that many large domain name registrars are based in the United States gives the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control, or OFAC, control “over a great deal of speech — none of which may be actually hosted in the U.S., about the U.S. or conflicting with any U.S. rights.” “OFAC apparently has the power to order that this speech disappear,” Professor Crawford said. devamı: www.nytimes.com/2008/03/04/us/04bar.html?en=6df7aa0e243f6e66 |

|

boşlukları doldurun

bunlara da göz atabilirsiniz:

|

| otarafa: izlemeyennere | butarafa: forbidden zone |

| iletişim - şikayet - kullanıcı sözleşmesi - gizlilik şartları |